Infra

James Ford: The Elizabeth Line is a hit – so when can we expect London’s next big transport project? | Conservative Home

James Ford is a public affairs consultant. He worked as an aide to the Mayor of London, Boris Johnson, at City Hall between 2010 and 2012.

The Elizabeth Line has recently celebrated its second birthday. A vast undertaking – 73 miles long, 41 stations, and 13 years of construction – that has had a genuinely transformational impact. In the past year, around 210 million passengers used the service with a record 787,000 people using the line on a single day in April 2024. And its impact stretches beyond mere passenger numbers – the project is estimated to have directly impacted the creation of 55,000 new homes and boosted the London economy by £42 billion.

The Elizabeth Line is a testament to what transport infrastructure can achieve in economic development and public policy impact, not just in improving the quality and frequency of journeys made but also in terms of catalysing both housebuilding and job creation. The Elizabeth Line also has the highest customer satisfaction levels of any of London’s transport modes. Perhaps just as importantly given the parlous state of TfL finances in recent years, the popularity of the Elizabeth line generated £29 million more in fares during its first year of operation than was projected.

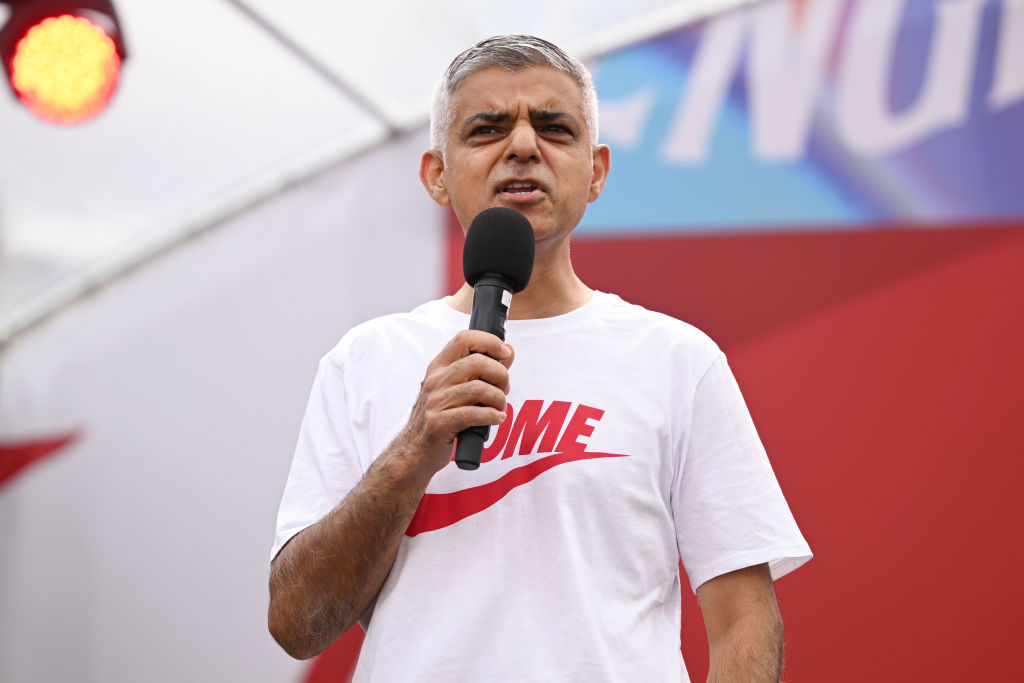

Perhaps we can ignore the irony of Sadiq Khan taking an unearned, self-congratulatory victory lap regarding the success of the Elizabeth line – as he did in his election campaign – given, on Khan’s watch, the project was delayed by four years and its cost ballooned by £4.3 billion. But the triumph of the Elizabeth Line serves as a wider, and more damning, criticism of Sadiq Khan’s failed approach to delivering new transport infrastructure for London. What is the capital’s next big project? And when will it open?

According to the latest (2021) iteration of the London Plan – the statutory spatial development strategy for London – the biggest proposed transport project is Crossrail 2 (sometimes called the Chelsea-Hackney Line). Described as “essential to London’s future” in the London Plan, Crossrail 2 is a proposed tube line that would run from north of London (from New Southgate and Broxbourne) to the southwest of the capital (ending in Chessington, Shepperton and Epsom), running through Dalston, Euston, Tottenham Court Road, Chelsea and Clapham Junction. Crossrail 2 is projected to carry 270,000 people a day at peak times, unlock 200,000 new homes and create 200,000 new jobs.

When can we expect this grand project to open? Well, the London Plan only goes so far as to say Crossrail 2 “aims to open in the 2030s” whilst Sadiq Khan’s own manifesto pledges to “continue work to safeguard the Crossrail 2 route so that this much-needed project can be brought to fruition in the future”. (Given that the core route for Crossrail 2 has actually been safeguarded since 1989 and the current full route safeguarded since 2015, this is probably the easiest – and most meaningless – manifesto pledge ever made). When serious plans were first brought forward in 2015 – when Boris Johnson was still mayor – construction was due to start in 2023. (It didn’t). Transport for London maintains a website for Crossrail 2 but the most recent press release on the site was posted in October 2022. The project gives every impression that it has been mothballed. Considering that a southwest/northeast tube line was first proposed in 1901 – with revised plans produced in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s – it is fair to say that progress has been depressingly slow.

However, despite this conspicuous lack of progress, it may surprise you to learn that Sadiq Khan has been taxing London businesses to pay for Crossrail 2 for five years already. The Mayoral Community Infrastructure Levy 2 (MCIL 2), which effectively taxes planning gain (specifically net additional floorspace) across London, was introduced all the way back in 2019 to fund Crossrail 2. MCIL 2 replaced, unsurprisingly, MCIL 1 which was introduced in 2012 to raise £600 million towards the costs of the Elizabeth Line’s construction. A 2022 study found that MCIL1 and MCIL 2 combined receipts had raised just under £1.09 billion. Taxing businesses for a transport project that is making no progress could, at best, be described as chutzpah and, at worst, fraudulent.

There are other – smaller and less ambitious – transport infrastructure schemes in both the London Plan and Sadiq Khan’s manifesto: Extending the Bakerloo Line to Lewisham south east London (projected to facilitate 65,000 peak time journeys and create 25,000 homes and 5,000 new jobs), extending the Docklands Light Railway to Thamesmead (25,000 new homes and 10,000 jobs) and the West London Orbital (16,000 new homes).

These projects could all be delivered more quickly and cheaply than Crossrail 2. They either involve repurposing existing lines or minimal construction of new lines, tunnels and stations. However, whilst these are easier to deliver than Crossrail 2 and would produce enhanced transport outcomes to local communities, they are also far less transformational for the capital and its economy as a whole and would constitute far less of a strategic boost to transport capacity than Crossrail 2 would.

Major transport infrastructure projects take time. The Elizabeth Line was first proposed in 1941 and first debated in Parliament in 1991. Government backing came in 2005 when Ken Livingstone was Mayor and construction started in 2009 during Boris Johnson’s tenure at Cit Hall. Major infrastructure projects also require political will. Ken Livingstone had profound shortcomings as Mayor of London, however – by securing government support for both the Elizabeth Line and the 2012 Olympics – he must be credited with driving forward major projects with huge impact, even though he must have known he might not have still been in office to open them or the spend the fare revenue generated.

Sadiq Khan may have only just been re-elected, but he is already running out of time to deliver a meaningful transport legacy. After the General Election, Sadiq Khan urgently needs to make up the time lost during his first two terms and secure government support for Crossrail 2 and the other transport projects in the London Plan. Is it acceptable that, after what will be the longest tenure of any Mayor of London, that Sadiq Khan’s transport legacy really could be that he simply cut the ribbon on a project that his predecessors did all the hard work on?